Share article

Ten years ago, tens of thousands of Syrians dared to rise up against the Assad dictatorship that had ruled for 40 years. Protests quickly broke out in many parts of the country, the vast majority of which were peaceful. At first, the demonstrators only called for reforms and an end to corruption – later, they demanded the fall of the regime. The state responded violently, triggering a chain of events which displaced half the country's population and allowed the terrorist militia, the "Islamic State", to take control of large parts of Syria and Iraq. As time went on, more and more other countries got involved in the war. Today, about half a million people have been killed, and tens of thousands have disappeared into the prisons of Syria's intelligence services.

Autocracy and Sectarianism

For a long time, most observers considered it unlikely that mass protests would break out in Syria. Back then, the country on the Mediterranean Sea was even nicknamed the "kingdom of silence”. In the 1980s, the Assad regime had virtually wiped out all opposition, both secular and Islamist. Syria's long-time defense minister, Mustafa Tlass, estimates the number of political prisoners executed during this time to be as high as 150 per week – in Damascus alone. He told the German newspaper, "Der Spiegel", in a 2005 interview, "If you want to stay in power, you have to scare the others." When the Islamist "Muslim Brotherhood" began an uprising in the late 1970s, the army ended it by massacring no less than 10,000 people in the city of Hama in 1982. The carnage and merciless violence in the detention centers silenced most of the opponents of the regime for decades.

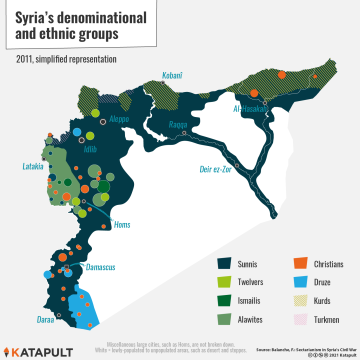

Syria was a very diverse country before the war. Sunni Muslims made up the majority of the population, but there were also Islamic minorities such as Alawites and Shiites, as well as Christians and Druze. About ten to 15 percent of the population was ethnically Kurdish.

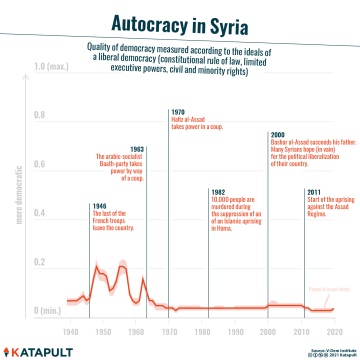

After Syria's independence, the Alawites were socially marginalized. Only a few institutions offered them opportunities for advancement, including the army and the Arab-nationalist Baath Party. In 1963, the Baath Party seized power by way of a coup d'état. However, internal party conflicts festered in the background, and the next putsch followed quickly thereafter. In 1970, Assad finally ended the struggle for power in the Baath Party and Syria when he orchestrated a final coup.

Assad, himself an Alawite, established a brutal regime that relied heavily and increasingly on confessional and tribal networks. He did not care about religion; for him, it was about power. Assad filled central positions within the army with his own followers and relatives. By doing so, he assured that the loyalty of the armed forces would lie first and foremost with him and his regime.

While economic living conditions in Syria generally improved, Assad's rule brought no particular benefits to most Alawites. The army, intelligence services and bureaucracy remained their best means of a steady income and upward social mobility. As a result, Alawites became the face of the hated, oppressive state apparatus. Many of them supported the Baath regime's brutal crackdown on all opposition out of fear of being marginalized again in the event of another regime change. Alawites were also consistently disproportionately represented in many opposition parties and groups.

Hafiz's son, Bashar al-Assad, took power in 2000, and under him, Alawites became even more dominant in security services. 20 of the 23 commanders of the Syrian armed forces before the war were Alawites. All eight directors of the two influential military intelligence services between 2000 and 2011 also belonged to his sect, as did all of the commanders of the Republican Guard. But unlike his son, Hafiz had also won over many Sunni farmers by means of agricultural reforms. Bashar, on the other hand, pushed neoliberal reforms that drove many people into poverty, and his government continued to repress its citizens. Torture remained the method of choice to silence dissidents, but the regime also instrumentalized social divisions to maintain its own power and pitted segments of the population against each other. For example, it fueled the minorities' fear of the Sunni majority. And when unrest broke out among the Kurdish population in Qamishli in 2004, the regime armed local Arab tribes to put down the protests.

Escalation

In 2011, there were widespread protests from the population, despite previous doubts that they would ever occur. Too much anger and frustration had built up, and it needed to be released. Young people in particular, who had not experienced the devastating repression of the 1970s and 1980s, hoped for change in light of the successful revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, often underestimating the violence the regime was prepared to use to maintain its power.

Assad portrayed the protesters as Islamists and terrorists and, through this method, sought to bring religious minorities to his side. The protesters reacted by repeatedly emphasizing that they were not terrorists and that not only Sunni Muslims were demonstrating against the regime. Christian crosses were presented alongside Islamic crescents at demonstrations. People marched in the streets with slogans such as, "One, one, one, the Syrian people are one!"

However: The decades-long suppression of all opposition had also resulted in the absence of any organized body that could have acted as a moderator. Many activists tried to network and organize themselves. They established common mottos for Friday demonstrations, for example, and documented the protests, as well as the violence of the regime. But it was often the Islamists who were able to gain influence more easily due to their advantageous financial standing.

When sections of the regime's opponents armed themselves in the face of government violence, large sums of money flowed from Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to the most reactionary elements of the opposition. They quickly dominated on the battlefield and began targeting democratic opposition figures. In a Damascus suburb, for example, the Saudi-backed "Army of Islam" led the forced disappearance of human rights lawyer and Assad opponent, Razan Zaitouneh, an icon of the democratic opposition. These extremists often characterized their struggle as a religious war against the Alawites. Nothing could have helped Assad more because now Syria's minorities were truly threatened, and he could cast himself as the lesser evil. In addition, the collapse of the state, massive violence and increasing poverty led many people to retreat to their original ethnic communities, as a return home was coupled with the promise of physical and social security.

State Terror

The Assad regime has violated nearly every element of international humanitarian law in Syria. "Assad – or we burn the country down" became the rallying cry of militiamen loyal to the regime. Thousands of political prisoners were tortured to death in prisons. More than a million people were living in places that were temporarily besieged – the majority of them by the Syrian military. The combination of starvation and permanent bombardment was intended to drive communities into submission. And it worked: Gradually, this approach succeeded in capturing one insurgent area after another.

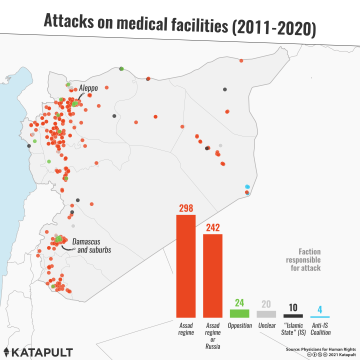

Part of this strategy included attacks on hospitals and medical personnel. The organization, "Physicians for Human Rights" states, "Health workers and other civilians have been relentlessly and unlawfully targeted, and international laws and treaties have been blatantly disregarded." The regime was responsible for the overwhelming number of attacks on medical facilities, which were intended to spread a sense of total insecurity among the population. At least 930 doctors and nurses have been killed since March 2011 – about 91 percent of them by the Assad regime and its closest ally, Russia. Through its intervention in Syria, Moscow has succeeded in establishing itself as an unavoidable power in the Middle East.

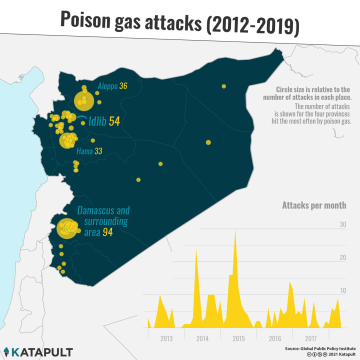

The regime also repeatedly deployed poison gas, most commonly, chlorine gas. Many people sought shelter in basements during bombing raids, but these chemical warfare agents are heavier than air and thus sink to the ground and penetrate into basements. The use of these weapons also contributed to the sense of total insecurity and sent a signal: There are no safe places; the only way out is submission. By spring 2019, the United Nations was investigating 37 poison gas attacks in Syria from 2013 to 2018. In 32 cases, it gave the blame to the Assad regime.

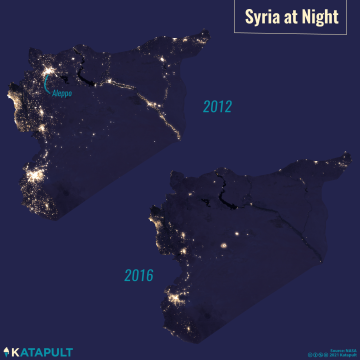

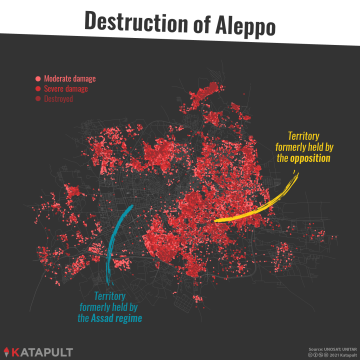

This scorched earth policy can be seen in satellite images of Aleppo, the country's largest city. During the war, it was divided into two parts. Analysts from the United Nations identified heavily damaged or completely destroyed buildings in the metropolis. They found the most substantial destruction in the once rebel-held eastern part of the metropolis, where the Syrian air force dropped countless bombs.

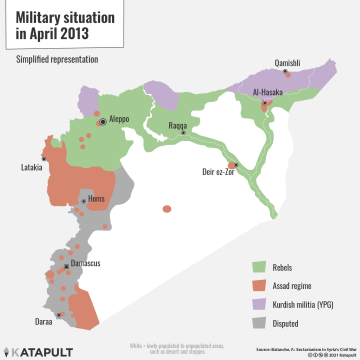

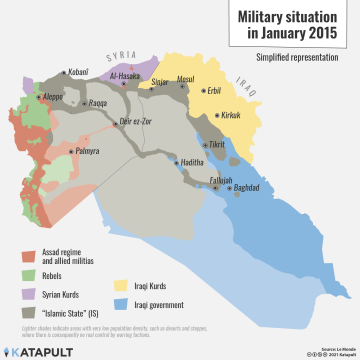

The opposition failed to establish effective administrations in nearly all of the cities it took control of from the regime. The rapid disintegration of order attracted jihadists from other countries, such as Iraq, who sensed an opportunity for a power-grab amidst the Syrian chaos – including the terrorist militia, the "Islamic State". It exploited the power vacuum to bring large parts of the country under its control and establish a regime of terror that quickly encompassed large parts of Iraq and Syria.

International Aerial Warfare

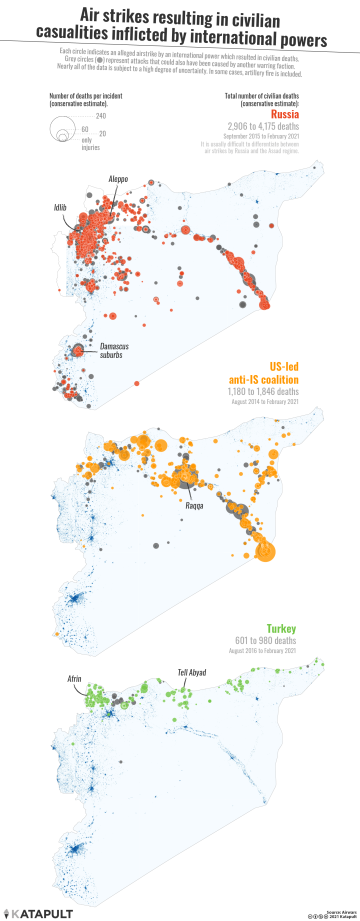

It was precisely the rise of the "Islamic State" that led the United States to become increasingly involved in Syria. While the U.S. had previously provided half-hearted support to some rebel militias, from the summer of 2014 onward, it brought the full weight of its military upon the jihadists, often acting ruthlessly in the process. Thousands of civilians died in bombing raids by the American-led coalition, which also included France, the U.K. and Germany. According to the organization, "Airwars", at least 1,180 people were killed in Syria – a conservative estimate. By this point, Washington’s call for Assad to step down had clearly become political posturing, if it had not been that already.

Russia intervened in the war on the side of the regime in September 2015 and launched tens of thousands of airstrikes against rebels and the "Islamic State". Prior to that, Iran and militiamen loyal to it from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan supported the regime on the front lines. Moscow also repeatedly bombed residential neighborhoods and medical facilities, according to detailed reports by "The New York Times". Conservative estimates from "Airwars" place the number of civilian casualties resulting from Russian aerial warfare at between 2,906 and 4,175 people. During all of this, Moscow provided cover for the Assad regime in the United Nations Security Council, blocking resolutions that would have put further pressure on it.

The U.S. found allies on the ground in the form of the Kurdish-Arab military alliance called the "Syrian Democratic Forces" (SDF), who now control almost the entire northeast of the country. However, Turkey accuses the SDF of being closely linked to the Turkish Kurdish militia, PKK, which Ankara has been waging war against for decades. Three military interventions by Turkey in northern Syria were directly or indirectly targeted at the SDF. In spring 2018, for example, they seized Afrin in northwestern Syria. In the fall of 2019, Turkey occupied an additional part of Syria centered around the city of Tall Abyad.

Syria Today

Ten years after the protests began, large parts of Syria lie in ruins. But the conflict is still not over. What will become of the Turkish-occupied zones in the North is still unclear, as is what form the self-government of the SDF will take. The fate of the Idlib province, to which hundreds of thousands of civilians and fighters have been driven, is also uncertain. The former al-Qaeda offshoot, "Hai'at Tahrir al-Sham", currently dominates the region. It, too, has successfully established a regime of fear by murdering many of its critics. Among them was most likely the activist and citizen journalist, Raed Fares, who became internationally known for satirical protest banners written in English. Thus, the people who originally led the revolution were killed or expelled in recent years: where Assad failed to do this, the terrorists succeeded.

Formally, the country is largely under the rule of Assad again, who so far has been as uncompromising as ever in dealing with his critics – even when they come from his own ranks. Beneath the surface, the societal tremors continue. Iran and Russia are vying for influence. Tens of thousands of young men have been killed on the front lines. In many Alawite communities, their absence from the urban landscape is evident. Syria's economy is also in shambles: Industrial centers, like Aleppo, have been destroyed, oil-rich areas are under SDF control and the Lebanese banking system that stored large amounts of Syrian money collapsed in 2019. On top of all of that, Syria is also under international sanctions. And yet, with the support of Russia and Iran, Assad has managed to at least partially reinstate the sense of fear that made open protest inconceivable for so long.

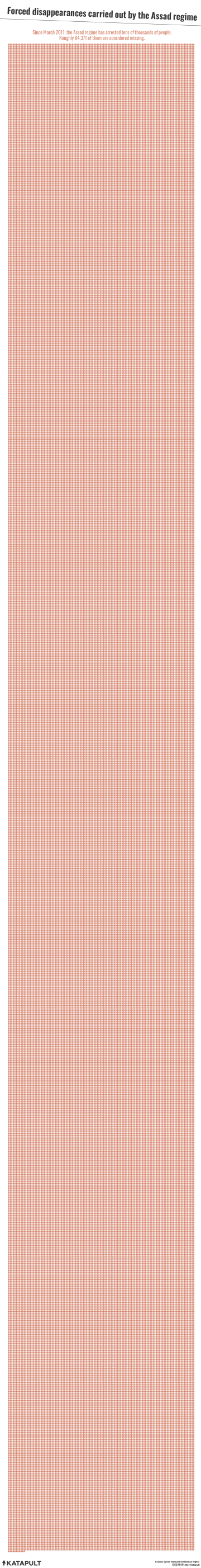

For the time being, there is a deadly silence in Syria. A silence that can be seen in the unresolved fates of almost 100,000 people, whom the warring parties have made disappear. The Assad regime alone arrested around 84,000 people who never reappeared. Human Rights Watch analyst, Nadim Houry, quotes a Syrian deserter who described the purpose behind these acts, "Detaining someone limits their ability to act, but disappearing them, paralyzes the entire family. The family will divert all their energies to finding them. As a tool for control, it can hardly be beaten."

Aktuelle Ausgabe

Authors

Jan-Niklas Kniewel

KATAPULT

Translators

Geboren 1994 in den USA. Seit 2020 Redakteur bei KATAPULT. Zuvor Studium der Musik und Linguistik/Germanistik an der University of Alabama. Teamleiter von @katapultmaps.