Share article

On November 21, 2013, the protests in Kiev now known as the "Euromaidan" began. After that, events spiraled out of control: The president at the time, Viktor Yanukovych, fled, and Russia invaded Crimea. From that point on, there was a war in eastern Ukraine. A war which Europe had apparently long forgotten - until now. For several weeks now, Ukraine has again made headlines on an almost daily basis. There is growing concern about an armed conflict in Ukraine between Russia and the NATO member states. But why is Ukraine so important to Russia?

The Forgotten War

Ukraine was formerly one of the 15 states of the Soviet Union and became an independent state after its disintegration. Ukrainian is spoken in most of Ukraine, while Russian is spoken in some parts. Because of its location, Ukraine is an important connecting country between Russia and the European Union, in part because it is a transit country for gas supplies.

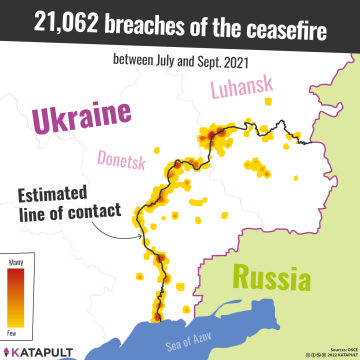

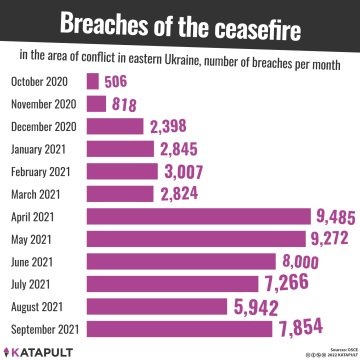

In the affected areas of eastern Ukraine, the war continues to shape everyday life to this day. On the one side are the pro-Russian separatists who want to secede from Ukraine. They founded two new people's republics: Luhansk and Donetsk. Both, with a combined total of almost five million residents, are not recognized internationally. Foreign Offices have already advised against entering the country. Soldiers are stationed along the borders on both sides. The long-standing ceasefire has not been in effect since the beginning of 2021. Eastern Ukraine is also one of the most heavily landmined areas in the world. The five border crossings are also littered with mines. The aid organization Médecins Sans Frontières has set up mobile toilets at the border crossings, as it is life-threatening to go into the bushes. 720 people have lost their lives in mine accidents since the beginning of the Ukraine Conflict.

Turning Point: Euromaidan

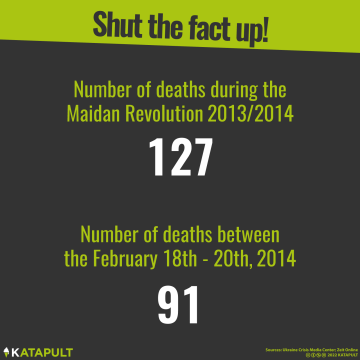

Between late November 2013 and February 2014, thousands of people protested in the cities of Ukraine. The protests were directed against then-President Viktor Yanukovych. He was negotiating an EU association agreement, but then surprisingly backed out and did not sign it. With this decision, he clearly sided with Russia. This move by the president was the trigger, but not the only reason, for months of mass protests by Ukrainian society. Some of the protests were also violent, with around 100 people dying in total.

The protests were held as a result of widespread dissatisfaction among the Ukrainian population, especially with the corrupt president and his increasingly authoritarian style of government. The society hoped that an orientation toward the West would lead to more democracy, higher living standards and further democratic development. The democracy developed in the streets.

What incentives there were for Yanukovych not to sign the treaty after all is unclear. What is clear is that he - like his predecessors - always conducted negotiations in both directions. Sometimes he moved closer to the EU, sometimes to Russia. With this tactic, Ukraine often received loans and subsidized gas supplies from Russia at important moments, and this was also the case shortly before the signing of the treaty.

According to Russia: The Euromaidan protests were organized by the West, more precisely: by the United States. The Russian government also claims that the majority of Ukrainians do not want any rapprochement with the EU at all. There is also speculation about possible Russian influence, but there is also no evidence to be found. Some right-wing extremists among the protesters have attracted the attention of the media and political observers. But overall, experts from the Heinrich Böll Foundation conclude that the Euromaidan is not an extremist movement, but a liberal mass movement of civil disobedience.

The Escape of the President

Yanukovych fled to Russia after the unrest began. An interim government signed the agreement with the EU that Yanukovych had rejected. Russia considered the change of power in Kiev illegitimate. As a result, new problems arose. They revolve around the Crimean peninsula. It belongs to Ukraine, but has cultural and geographical ties to Russia. Most of the population there speaks Russian, and Russia's Black Sea fleet has its home port in Crimea. Putin annexed Crimea because he said it had always been Russian. Which is not true. Although Russia did conquer Crimea in the Russo-Turkish War in 1747, and the Crimean population has felt a sense of belonging to Russia ever since. Under Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, the then head of government of the Soviet Union, it was annexed to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in 1954. As long as the Soviet Union existed, there were no problems between Ukraine and Russia. After the fall of the Soviet Union, things looked different.

The annexation of Crimea violated several international treaties. The Kremlin made the decision in favor of annexation on February 23, 2014. Four days later, the military was already in Crimea. On March 6, the Parliament of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea decided to join Russia. Ten days later, Crimea held a referendum on this issue, in which allegedly more than 95 percent of the Crimean population voted in favor of belonging to Russia. However, the referendum was not under international scrutiny, so no one knows whether it actually reflected the will of the people. In March 2014, the treaty between Russia and Crimea was ratified. Since then, Russia has referred to Crimea as part of its own territory. The annexation happened so quickly that it caught the West and Ukraine off guard.

Then protests began in eastern Ukraine. Pro-Russian demonstrators occupied administrative buildings there, took control of the region and demanded independence from Ukraine. The Russian government allegedly supported the protests, according to accusations from the West and Ukraine. Moscow claims it had to protect the Russian population in Ukraine.

The armed conflict has been taking place in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions since 2014, with the Ukrainian army attempting to retake the territories. The U.S. is helping Ukraine to do so. Russia supports the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk with weapons and money. Russian soldiers are also fighting in eastern Ukraine. More than 13,000 people have died since the war began. More than half a million Ukrainians have fled to other states and about a million have fled the war within Ukraine.

Almost 40 million people live in Ukraine. About eight million are Russians. Most Russian speakers live in eastern Ukraine. About 20 percent of the Ukrainian population speaks Russian or a language other than Ukrainian. In 2019, Russia began issuing Russian passports to people in eastern Ukraine. For Western observers, even this was a sign of escalation.

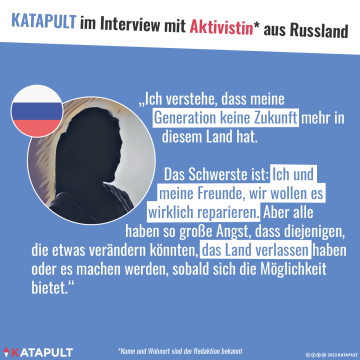

For Russian President Vladimir Putin, Ukraine is very important in the struggle between Russia and the United States over Europe. There are close ties with the country. Also from a strategic point of view: Russia does not want more democracy right on its doorstep. That would make it more difficult for Putin to exert influence in neighboring countries. The Russian population sees things differently. Most people in Russia have other problems to worry about: rising prices, falling incomes. Ukraine is also weary of war. The country's population remains divided. More than half have a positive attitude toward the EU. More than a third have a positive attitude towards the U.S. About one in five, on the other hand, has a positive view of Russia. Even more, however, have a negative view of Russia.

Military at the Ukrainian Border

With troops at the Ukrainian border, Putin has at least achieved one thing: Western politicians are negotiating with him on an equal footing. For years, Putin has accused the Western alliance of expanding ever further in the direction of Russia. He demands a stop to this eastward expansion of NATO. No one assumes that NATO will go along with this. But Russia is also concerned about agreements and guarantees, some of which were made right after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Many of these were not recorded in writing, but were made verbally. In an analysis, the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (German Institute for International and Security Affairs) says that this type of military show of force in diplomatic matters is a typical Russian strategy.

Russia has been showing its power for a long time. Since the spring of 2021, there has been a massive buildup of Russian troops along the Ukrainian border; around 100,000 soldiers are now said to be stationed there. The West is reacting clearly: It is calling on Russia to respect its borders and is warning of an escalation. The Russian leadership denies plans for a military offensive. Nevertheless, it is the strongest concentration of military at the Ukrainian border in years. Meanwhile, the U.S. has also increased its troop couint in Germany and Eastern Europe. A new Cold War is looming.

What will happen next? Political scientist Margarete Klein, of the Stiftung für Wissenschaft und Politik, describes possible military scenarios. Russia could further increase the pressure on NATO by stationing troops in Belarus. Second, Russian soldiers could invade the Donbass. The government is already controlled by pro-Russian separatists. Klein does not rule either of the scenarios at present. However, Russia has already gambled away the possibility of a face-saving solution with NATO, in Klein's opinion.

Should Germany Supply Weapons or Not?

Germany plays a major role in the Minsk Agreement (Minsk II). It was co-signed by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2015. It established the ceasefire in Ukraine and security zones between the separatists and the rest of Ukraine. It also established the self-governments of the seceded territories. The agreement is supposed to regulate that things will proceed peacefully between the proclaimed republics of Luhansk and Donetsk and Ukraine. If Germany were to intervene militarily in the conflict now, the agreement would be in jeopardy. This is one of the reasons why Germany is so reluctant to supply weapons. Furthermore: The new governmental coalition in power in the German Bundestag has stipulated that it will not allow any arms deliveries to crisis areas.

But many assign responsibility to Germany as the most powerful and largest EU state in Europe. Radek Sikorski, a security expert and former Polish foreign minister, sees Germany's hesitancy on the question of whether or not to supply weapons as a weakness. He said that Germany had made itself even more dependent on Russia by hastily phasing out nuclear power and building the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. According to Sikorski, Russia built the pipeline with the aim of being able to blackmail the Central Eastern European states sooner or later. That time has now come, he said. Experts are currently warning that gas reserves for Germany are extremely low. Russian gas is considered to be urgently needed.

Dependent on Russia

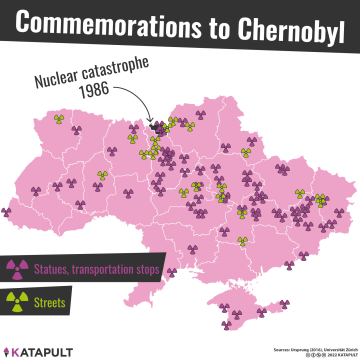

Ukraine is also dependent on Russian gas, but wants to change that. It sees one possibility in nuclear power, to which it has stuck even after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, Ukraine is more dependent on nuclear energy than ever before. In 2020, 15 nuclear power plants were operating in the country. Nuclear power accounts for about 50 percent of electricity production. And this despite the fact that Ukraine suffered the worst nuclear accident in history.

Currently, more and more countries are intervening in the conflict to mediate between the US and Russia. Some NATO countries have pledged to supply weapons, and some are supporting Ukraine financially. The U.S. pledged support to Ukraine immediately after the first reports of Russia's military on the border. Most recently, even German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced his intention to speak with Putin in person. Nevertheless, the fronts remain for the time being and an invasion of Ukraine by the Russians has not yet been ruled out.

Wir werden ein Newsteam aufbauen – mit Leuten, die in der Ukraine bleiben, mit welchen, die gerade nach Deutschland flüchten, und mit welchen, die in die Ukraine reisen werden. Ab und zu wird gedruckt.

Authors

Geboren 1994, ist seit 2021 Grafikerin bei KATAPULT. Sie hat visuelle Kommunikation in Graz studiert und ist Illustratorin.

KATAPULT-Redaktion

Ehemalige Redakteurin bei KATAPULT. Hat Onlinejournalismus und Humangeographie in Darmstadt und Mainz studiert.

Translators

Geboren 1994 in den USA. Seit 2020 Redakteur bei KATAPULT. Zuvor Studium der Musik und Linguistik/Germanistik an der University of Alabama. Teamleiter von @katapultmaps.